Just before Alec Raeshawn Smith turned 24, he thought he had come down with the flu. When he went to the doctor a few days later, staff immediately tested his blood sugar levels. They were dangerously high—Smith’s body had stopped producing insulin, a vital hormone that allows the body to turn the glucose in food into usable energy.

Like 1.25 million other Americans, Smith was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes. Unlike Type 2, a more common condition sometimes linked to high body weight, Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease caused when white blood cells attack the pancreas, killing insulin-producing cells. There is no cure for Type 1, and it can’t be treated with pills or other noninvasive procedures; artificial insulin must be injected into the patient several times per day.

“Without insulin, people with Type 1 diabetes will die,” said David Nathan, a professor at Harvard Medical School, in an interview with the HPR. “And not over a long period of time, but over the course of a week.”

For Smith, then a server at Khan’s Mongolian Barbeque in Richfield, Minn., the diagnosis was life-changing. At first, he had trouble maintaining his active lifestyle—Smith loved hiking, fishing, concerts, Minnesota sports, and playing with his young daughter Savannah—but in time his nutritionist and endocrinologist helped him bring his diabetes under control.

For two years, Smith managed his condition relatively well. But it wasn’t easy financially, even after he was promoted to manager. Doctor visits combined with the expensive life-preserving drugs added up, even with insurance. Copays usually totaled between $200 and $300 a month. Smith occasionally had to borrow money from his mother, Nicole Smith-Holt, to pay for his medication.

On May 20, 2017, Smith turned 26, aging out of his parents’ insurance. Because he was a single man with a decent job, Smith didn’t qualify for subsidies under the Affordable Care Act. The most inexpensive plan Smith and his mother could find on the Minnesota exchange was around $450 per month with a $7600 deductible. Smith could have afforded the monthly premiums, but the deductible made the plan too expensive. Although the family had been researching plans for Smith since February, he had to go off of health insurance entirely.

When Smith went to the pharmacy to pick up his insulin in early June, the bill was over $1300 without insurance. He couldn’t afford the medicine that day, and decided to ration his remaining insulin until he was paid. Smith did not tell his family that he was adjusting his carbohydrate intake so he could lower his dosage.

“He knew the signs of being in trouble with his diabetes,” Smith-Holt told the HPR. “But when your body starts shutting down like that, you’re not making very clear, rational decisions.”

On June 25, Smith went to dinner with his girlfriend, where he complained about stomach pains. It was the last time anyone saw him alive. He called in sick to work the next day. On June 27, Smith was found dead in his apartment.

There are no generic insulins. Over the past twenty years, prices for the most commonly prescribed “analog” insulins have risen from about $20 per vial to well over $250 per 10 mL vial, an over 700% increase after accounting for inflation. In contrast, insulin today costs roughly five dollars per vial to produce. With deductibles far outpacing wages, insulin has become unaffordable even for well-off Americans.

The reasons for this price increase are as complicated as the American healthcare system. Carefully negotiated rebate systems have driven enormous increases in the list price for insulin, leading patients to pay far more than insurers for their treatment. High-deductible plans, designed using oversimplified microeconomics to encourage patients to shop for better prices, instead have driven people to decline potentially lifesaving tests and adopt dangerous practices like rationing. In a market where pricing is mind-bogglingly complex, where different entities pay different amounts for the same treatments, and where drugs are of life-saving importance, the American healthcare system has forced some diabetics to choose between death and financial ruin.

From charity to cash cow

Smith’s death would have come as a shock to the creators of insulin, who hoped their discovery would be available to all. Prior to 1922, Type 1 diabetes was a dreaded and incurable disease. Patients were prescribed an extremely sugar-deprived diet, so severe that many died of starvation before they died of diabetes; at best, the treatment prolonged life by a year.

On a shoestring budget at the University of Toronto, several young scientists began investigating a possible treatment in 1921—they found that by grinding up and purifying animal pancreases, and then regularly injecting the material, they could treat Type 1 diabetes in dogs. After first testing the drug for safety by injecting themselves, the scientists treated a 14-year-old boy with Type 1 diabetes. His recovery was almost miraculous, going from death’s door to good health in a matter of weeks.

By 1923, the scientists had won the Nobel prize and the treatment had entered mass production in collaboration with Eli Lilly and Company and the Swedish organization Nordisk. The scientists patented the drug and sold it to the University of Toronto for three dollars (one dollar for each researcher), thinking that this was the best way to ensure that affordable treatment would be available to everyone who needed it.

Today, treatment is more advanced than the original animal pancreas slurry. Fast-acting “analog” insulins were pioneered with Lilly’s Humalog in 1996, making use of a modified chemical structure that absorbs faster in the bloodstream. But when Novo Nordisk entered the market four years later with its own analog insulin, NovoLog, prices did not decrease due to competition. Instead, Lilly and Nordisk followed each other closely in an exponential price increase. When Humalog was first introduced, it cost $21. At the time of writing, HumaLog costs $295.35 per vial and NovoLog costs $296.27. The older “human” insulins like Humalin are less expensive, but far less effective in treating Type 1 diabetes — yet even these primitive insulins have increased dramatically in price since their introduction in 1982.

“There hasn’t been a molecule changed in them. There hasn’t been a bit of change in terms of their synthesis, their manufacturing, and yet the costs have gone up extraordinarily,” said Nathan. “There are no adults in the room to tell the companies they can’t charge whatever they feel like.”

However, drug companies are not the only ones who profit from this massive increase in list price. Around the 1990s, drug manufacturers and insurers began using middlemen called Pharmacy Benefit Managers to cut deals. PBMs were created to help negotiate discounts and rebates from drug manufacturers and maintain a formulary, the list of drugs covered by an insurance plan. But in the case of insulin, the complicated interests of PBMs have perversely driven list prices to historic heights. Actual net profit to drug manufacturers hasn’t grown by as much as the list price would suggest; instead, money is diffused between PBMs, insurers, and pharmaceutical companies. Only one group doesn’t benefit from this scheme: patients.

Twisted accounting

When an insured patient buys insulin, the complicated rebate system begins to turn its gears. If the patient is enrolled in a high-deductible plan, like 29% of workers with employer-sponsored insurance, they will pay full list price out-of-pocket until their deductible is met. After a set amount of time, the manufacturer will remit a rebate to the PBM worth around $200 at the time of writing. PBMs keep about 10% of this for themselves and pass the rest to the insurer.

From there, the story gets murky. Insurers, according to the PBM CVS Health, are trusted to use this rebate “to lower overall member benefit cost.” But no one enforces this theoretical insurer benevolence. What we do know is the patient often does not receive that rebate directly, even though they paid for the drug in full.

“While rebates negotiated between drug manufacturers and payers are intended to lower prescription drug costs for consumers, it does not appear that those savings are shared with them,” said Ashleigh Koss, a spokesperson for the insulin manufacturer Sanofi, in emailed comments to the HPR. Novo Nordisk’s spokesperson told a similar story.

When a patient under a high-deductible plan pays for insulin, they get hit by the almost $300-per-vial bill, while the healthcare corporations split the $200+ rebate. The drug manufacturer still pockets a hefty markup. If a patient is uninsured, the companies like Eli Lilly, Sanofi, and Novo Nordisk take home the inflated list price in full.

Insurers “have a perverse incentive to prefer a brand with a high list price and large rebates over a brand with a lower list price but smaller rebates,” said Julia Boss, president of the Type 1 Diabetes Defense Foundation, in emailed comments to the HPR.

For someone like Alec Raeshawn Smith, there was no way to win. While drug companies do offer price relief services directly to consumers, according to Nathan patients seem to be unaware of these programs or are unable to take advantage of them. Without this relief, Smith was stuck either paying a $1300 insulin bill directly to manufacturers or a $1300 bill split between manufacturers, his insurer, and a PBM.

None of the major PBMs—Express Scripts, CVS Health, or OptumRx—responded to requests for comment; neither did representatives for the insulin manufacturer Eli Lilly.

Sometimes the close relationship between PBMs, insurers, and manufacturers crosses a line—in 2011, the PBM Medco and manufacturer AstraZeneca colluded to place brand name heartburn medications on the Medco formulary, complete with $100 million in kickbacks.

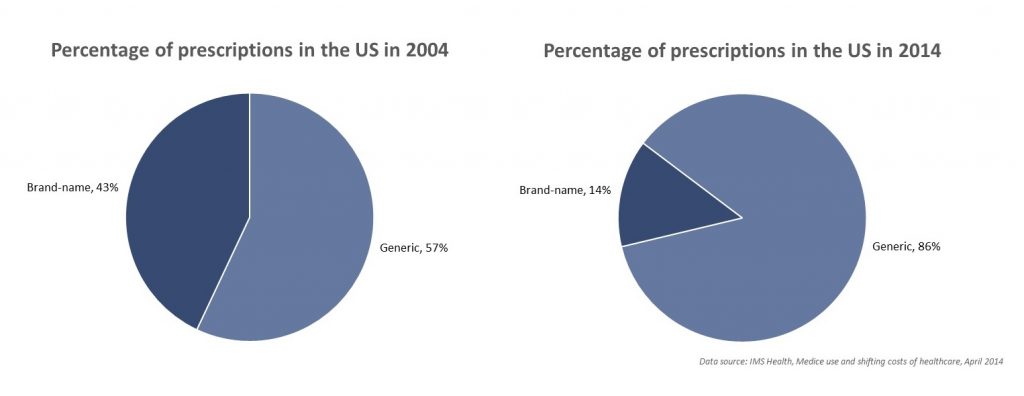

Diabetics have become a special target for this rebate scheme for a number of reasons. Over the past decade, the pool of rebatable drugs has shrunk. According to testimony from Patricia Danzon, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, the rise of generic drugs has forced PBMs to rely on larger rebates from a smaller number of prescriptions to maintain the same profit margins. Because there is no generic insulin, PBMs and insurers both have strong incentives to negotiate high list prices and rebates from manufacturers.

Diabetics have other vulnerabilities that can be exploited by these organizations. One is obvious: Type 1 diabetics will die without their insulin, and they die quickly. This makes patients nervous when challenging massive multinational corporations with little government help.

“It’s important here to understand how hard it is to stand up for civil rights and consumer protections in relation to powerful entities that that hold your life, or your child’s life, in their hands,” said Boss.

A lack of empathy

The public has stayed largely silent on insulin pricing issues. Industry has been successfully able to blame people with diabetes for high drug prices, claiming that if people “maintain a healthy body weight” drug prices would be lower. While it is true that Type 2 diabetes is linked to obesity, and that some Type 2 patients use insulin, these narratives conveniently report list price expenses, not the actual rebated cost to insurers. With this rhetorical flourish, attention is taken away from healthcare corporations and redirected towards patients themselves.

“There’s a lack of empathy there for all of us, Type 1 and Type 2,” said Peg Abernathy, a Type 1 diabetic and activist, in an interview with the HPR. On Saturday Night Live last year, comedians joked that McDonald’s was offering two versions of the Big Mac, one for each kind of diabetes. Besides being factually inaccurate—Type 1 diabetes has nothing to do with body weight and Type 2 diabetes is triggered by a myriad of other factors, including pregnancy and race — these comments underscore a culture of contempt in America towards long-term health issues.

Mick Mulvaney, the Trump administration’s director of the Office of Management and Budget, said last year that the government should “provide that safety net so that if you get cancer you don’t end up broke,” but later added, “That doesn’t mean we should take care of the person who sits at home, eats poorly, and gets diabetes.” This narrative is one of the main reasons why diabetes advocacy cannot get off the ground, while price increases for drugs like the EpiPen were met with wide public outrage.

“Americans tend to treat sudden catastrophic health crises (heart attack, cancer) as a matter of bad luck, but chronic conditions like diabetes as a matter of bad choices,” said Boss.

What lies ahead

The United States does not negotiate prices with drug manufacturers. The for-profit companies who are supposed to negotiate, PBMs, do so in their own interests and not the interests of patients. Patients are left powerless, and are shamed publicly for their weakness.

The winners in this game are predictable. Alex Azar, president of Eli Lilly USA during its unprecedented insulin price hike, is now Trump’s nominee for Health and Human Services. There is reason to hope—the FDA announced in December that they would expedite applications for a generic insulin. But unlike traditional generics, the infrastructure necessary to produce insulin is complex, requiring factories of modified cells.

Organizations like the Type 1 Diabetes Defense Foundation and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation are fighting to share rebates directly with patients, cutting out a cash cow for the industry. If the rebates are eliminated, US insulin prices begin to look more like those in Canada. But until something changes, Americans like Alec Raeshawn Smith will lose their lives because they can’t afford a 100-year-old drug.

“[Diabetes] is a treatable, manageable disease, and people shouldn’t be dying from it because they should be able to afford their life-saving medication,” said Smith-Holt. “Without it they die.”

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons