Updated: April 8, 2017, at 4:15 p.m.

In May 2016, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell published his memoir The Long Game, a personal reflection on his three decades in the upper house of Congress. Just months earlier, McConnell set into motion another long game, which finally ended today, and whose resolution will have an impact on the Senate, the Supreme Court, and the nation for years to come.

Soon after the death of Justice Antonin Scalia in February 2016, Barack Obama announced that he would nominate Scalia’s replacement. In response, McConnell declared that Republicans would not consider Obama’s nominee: “This nomination will be determined by whoever wins the presidency in the polls. I agree with the Judiciary Committee’s recommendation that we not have hearings. In short, there will not be action taken.”

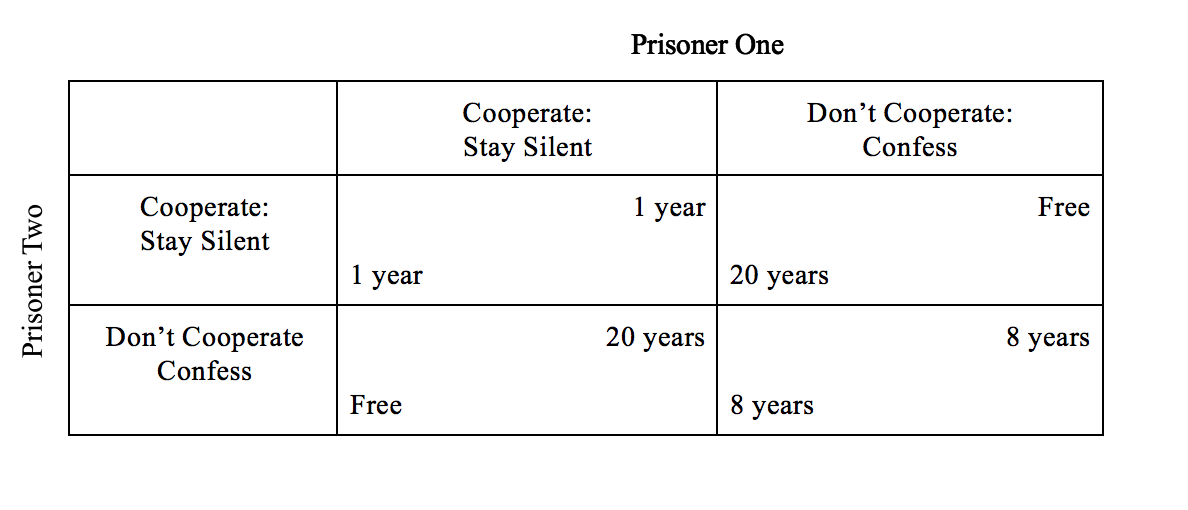

With those words, McConnell made the first move in a game known as the prisoner’s dilemma, an archetypal game theory contest that pits two parties against each other. The game, originally proposed by two RAND mathematicians and later formalized by the Princeton mathematician Albert W. Tucker, goes something like this: two criminals rob a bank and are arrested, imprisoned, and placed into solitary confinement. The police, who only have enough evidence to imprison the criminals for one year on a lesser charge, separately offer both criminals the same deal: “Right now, we can imprison you for one year. If you confess and betray your accomplice, we’ll let you go free, and imprison your accomplice for 20 years. If you both confess, we won’t need your testimony and will imprison you both for eight years.” What should the prisoners do?

The ideal scenario, of course, is that both prisoners stay silent and serve only one year in jail. But, game theory has a different outcome in mind. Held incommunicado, the prisoners don’t know what choice the other is going to make. Each wanting to go free, and each fearing that his accomplice might betray him, the prisoners act in their own self-interest and confess. Confession becomes the best choice for each prisoner, regardless of what his accomplice chooses*; by confessing, each prisoner ensures that he will either go free (if his accomplice stays silent) or serve 8 years (if his accomplice confesses, too), avoiding the possibility of 20-year imprisonment. After both prisoners realize that noncooperation is the best strategy, they confess to the crime. Both serve 8 years in prison, when they could’ve served just 1 year, if only they had cooperated.

The prisoner’s dilemma has been used as a model to understand a variety of competitive situations, including oligopolies, athlete doping, climate change, and even the classic ferryboat scene in The Dark Knight. We can now add the Senate battle over Scalia’s seat to that list. Over the past year, we have witnessed the prisoner’s dilemma play out, move-by-move, as Republicans and Democrats have fought over the ninth seat of the Supreme Court. And just as game theory predicts, the non-cooperative parties have produced a devastating outcome, the elimination of the longstanding Senate filibuster for Supreme Court nominees, also known as “the nuclear option.”

Partisans can bicker ad infinitum about which party cast the first stone in the years-long war over judicial confirmations and the filibuster, but there is no doubt that in the most recent game, it was the Republicans who made the first move. By refusing to consider Judge Merrick Garland’s nomination, Senate Republicans took game theory’s bait—they acted in their own self-interest, chose not to cooperate with Democrats, and tried their hand. The Republicans’ first opponent was Obama, and as Richard Lempert, a professor of law and sociology at the University of Michigan, wrote last year, the GOP’s move left Obama with three options: he could nominate a liberal, an extreme liberal, or a centrist. Ultimately, Obama went with the third option, known as the “minimax” strategy, whereby each party minimizes their loss.

By taking a moderate approach, Obama tried to induce the Republicans to cooperate with him and confirm Garland, who is considered a centrist judge with bipartisan appeal. The Republicans, however, still refused to cooperate, deciding not to give Garland a hearing and thereby preventing a majority-liberal Supreme Court. Senate Republicans’ refusal to consider Garland’s nomination and their subsequent elimination of the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees represent the most consequential changes to the Supreme Court confirmation process since the rejection of Ronald Reagan’s nominee Robert Bork in 1987. In refusing to considering Garland, Republicans set a precedent that the president of the United States cannot exercise his constitutionally-granted power of appointing justices in the final year of his or her presidency. In the end, Obama lost the game, and the Republicans went free.

Then, when President Trump nominated Gorsuch to fill the vacancy, Senate Democrats replaced Obama as the GOP’s opponent in the prisoner’s dilemma scheme. Soon enough, the battle over Gorsuch’s confirmation became a referendum on Garland, the filibuster, and the nuclear option: or in other words, a referendum on everything except for Gorsuch himself, who most believe is more than well-qualified for the position. After all, as the New York Times columnist David Leonhardt has written, “This debate isn’t really about qualifications. If it were, Gorsuch wouldn’t have been nominated, because Garland would be on the court.”

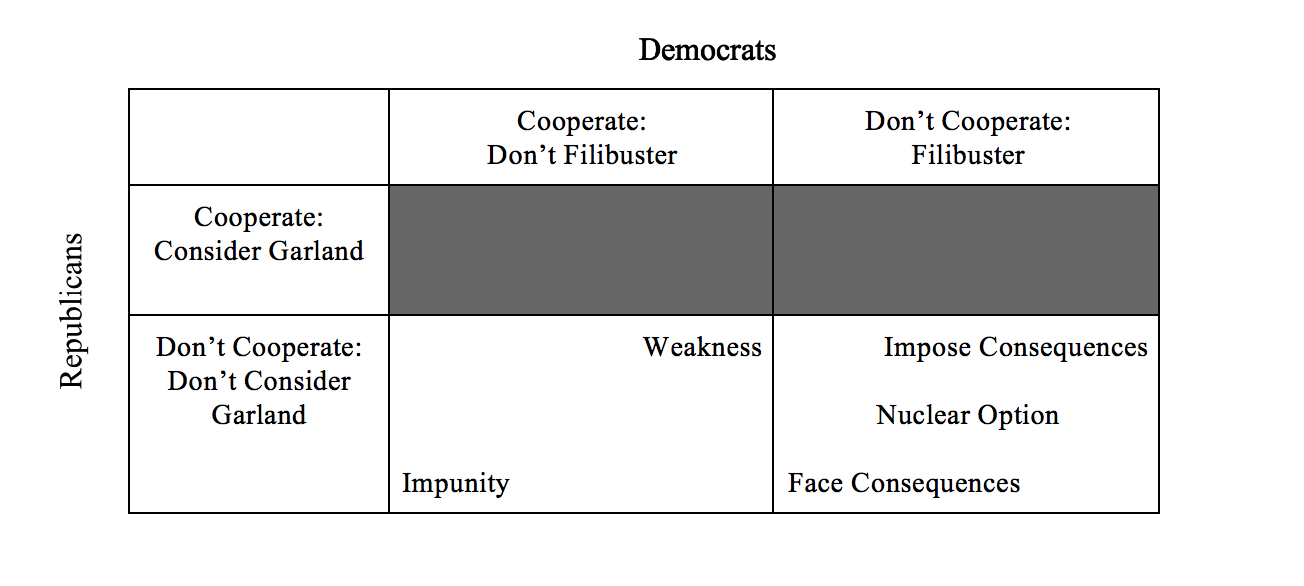

Looking at the battle over Gorsuch’s nomination through the lens of the prisoner’s dilemma, Senate Democrats had two options: either confirm Gorsuch (cooperate) or filibuster his nomination (don’t cooperate). The first option is what is known in game theory as the “sucker’s payoff.” Confirming Gorsuch is equivalent to the prisoner staying silent even though his accomplice betrayed him. Just as the silent prisoner’s cooperation gives him the short end of the stick, Democrats’ cooperation would have given Republicans a free pass for obstruction and illuminated the party’s weakness. So, just as game theory anticipates, the Democrats chose the second option and filibustered Gorsuch’s nomination. As a prisoner, if your accomplice betrays you, you may as well betray your accomplice as well—better for both of you to serve 8 years then you to serve 20 and your accomplice to go free. Through their filibuster, Democrats sent a clear message that they would not take Republican obstruction lying down, and that there would be consequences for the Republicans’ refusal to consider Garland’s nomination.

By choosing not to cooperate, Democrats forced Republicans’ hand. The GOP then invoked the “nuclear option” and eliminated the filibuster for Supreme Court confirmations. The outcome is bad for everyone involved. Both Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Anthony Kennedy are both over 80 years old, and Stephen Breyer is just two years away. Democrats face the risk that Trump will be able to appoint more ideologically extreme justices by a simple majority. Republicans will face the same risk when the tables eventually turn and a Democrat occupies the White House once again.

The nuclear option was not named in jest. Senator John McCain (R – Ariz.), the Republican maverick who has served in the Senate since 1987, put it this way when asked about the proposition that the nuclear option might a good thing: “Idiot, whoever says that is a stupid idiot, who has not been here and seen what I’ve been through and how we were able to avoid that on several occasions. And they are stupid and they’ve deceived their voters because they are so stupid.” By eliminating the high court filibuster, Republicans picked up where Senate Democrats left off. In 2013, led by then-Majority Leader Harry Reid (D – Nev.), Democrats effectuated a nuclear option of their own, eliminating the filibuster for all executive positions and low court confirmations—a move Republicans, frustrated by Democratic opposition to George W. Bush’s appeals court nominees, had first threatened in 2003. Now that the seal has been broken, it is not difficult to imagine even the sacred legislative filibuster being killed off at some point in the near future. The Senate—once known as the world’s greatest deliberative body, in which the power of the minority generated great compromises—is more and more becoming a contorted House of Representatives. As yet another vestige of the Senate falls victim to the disease of partisanship, it is the nation as a whole that suffers. As long as those in power play games with politics, the citizens will be prisoners to their partisan dilemmas.

Correction, April 8, 2017: An earlier version of this article identified Mitch McConnell as the Senate minority leader in 2016. McConnell has been the Senate majority leader since 2015.

Image Credit: Flickr / Phil Roeder Copyright 2.o