A recent report from the Social Security trustees forecasts the depletion of the nation’s largest social insurance program in 2034—one year earlier than last year’s report projected. Additionally, this year marks the first since 1982 in which the program is set to take in more than it will send out. Though this is not an immediate issue since the Social Security trust fund holds nearly $3 trillion in reserves, Social Security benefits cannot legally exceed the program’s annual income once those reserves run out.

Without reform, the report estimates that only 79 percent of scheduled benefits will be available when the program runs dry, cutting the amount of benefits old-aged and disabled Americans currently expect by hundreds of billions of dollars per year. The report once again serves as a reminder of why swift action on Social Security is essential.

A Worrying Picture

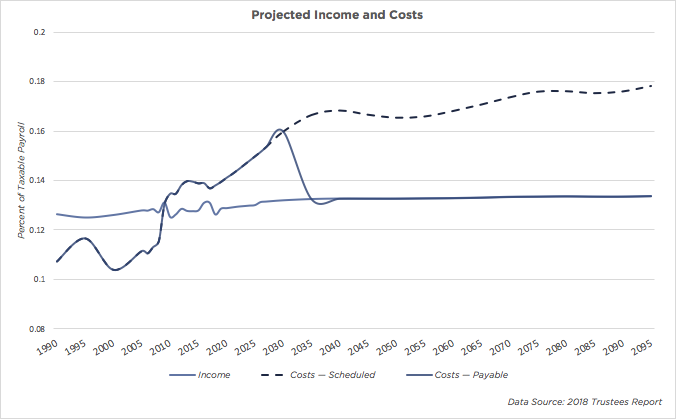

As the figure below shows, the outlook for Social Security is grim. Social Security costs, or the benefits the program sends out, are expected to continue to outgrow income. By 2034, however, when the trust fund runs out, costs will immediately drop to the level of annual income so the program does not enter into debt.

Though it is technically comprised of two separately-financed programs, Disabled Insurance and Old-Age and Survivors Insurance, “Social Security” typically refers to the hypothetical combination of both. Additionally, the hypothetical combined trust fund, which stores Social Security’s assets, is the OASDI trust fund. These hypothetical combinations are of interest because it is understood that should either fund empty, funds from the other will be transferred over. Given the relationship between the two funds, their combination is typically of greater interest.

Until 2034, Social Security is expected to continue running deficits, as is shown by the gap between the blue and gray lines. Starting that year, however, costs must equal the program’s income, meaning payable benefits will fall well short of scheduled benefits.

Though costs have exceeded income alone for years, this is the first year in which costs are expected to exceed income plus interest payments.

The primary factor behind OASDI’s financing shortfall is the aging of the American population. As ranks of baby boomers enter retirement, the labor force participation rate declines, and fertility rates reach new lows, a decreasing number of workers must pay for an increasing pool of beneficiaries. In addition, the trustees do not expect the baby boomer retirement wave to stabilize itself until 2039, years after the OASDI trust fund is set to become depleted.

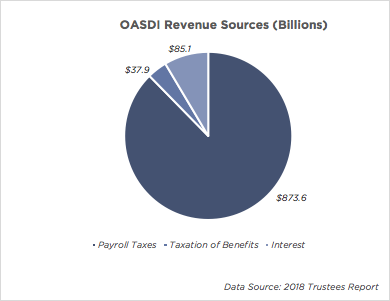

Though less significant than the population’s aging, an additional, largely-unanticipated factor weakening this year’s report was a decrease in estimated payroll tax revenue. As is seen in the chart below, the vast majority of OASDI’s income comes from payroll taxes, meaning the slightly lower-than-expected numbers have a substantial effect. In fact, the OASDI trust fund ratio, or the ratio of reserves to annual costs, dropped 33 percentage points this year, with 16 of those points attributed to low payroll taxes.

Two other changes unforeseen by last year’s report are the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and the rescission of DACA, a signature Obama-era immigration plan that allowed individuals brought to the United States illegally as children to obtain temporary work permits. Though the report does not indicate the estimated effect of each of these changes individually, it estimates that they reduce the trust fund ratio by 6 percentage points when combined.

Without providing the numbers, the report explains the mechanism through which each change affects Social Security. The tax cuts have opposing effects on the trust fund ratio. On the one hand, by repealing the individual mandate, these measures are expected to cause some individuals to drop their health insurance, increasing taxable income. On the other hand, lower tax rates mean less tax revenue from Social Security benefits, which is allocated to OASDI. In the short run, by contrast, the rescission of DACA has an unambiguous negative effect on the trust fund ratio; all of those affected by that policy, the “DREAMers,” were young, meaning they represent a source of income to the trust fund. By removing temporary work permits, DACA’s rescission exacerbates the financing shortfall.

Reform: The Sooner the Better

In order to preserve Social Security for the next 75 years—the length of time over which the trustees make their projections—Congress must enact one of four potential reforms. First, Congress may elect to increase payroll taxes by 2.78 percentage points, raising the combined employer and employee tax rate from 12.40 percent to 15.18 percent. Alternatively, Congress could reduce benefits by 17 percent to all current and future beneficiaries, or—thirdly—by 21 percent to newly-eligible beneficiaries alone. Each of these reductions, however, would have catastrophic effects on the well-being of retirees, many of whom almost entirely rely on Social Security payments for their source of income. Lastly, Congress could implement some combination of these three, dividing the blow between current and future beneficiaries and current taxpayers.

Delaying action only makes the problem worse. If reform is delayed until 2034, the trustees estimate, 75-year solvency requires either increasing taxes not to 15.18 percent but to 16.27 percent, or reducing benefits not by 17 percent but by 23 percent. In fact, by that year, even completely eliminating benefits to future beneficiaries would not alone secure solvency.

The primary reason why delayed action exacerbates the financing shortfall is that each year a cohort of baby boomers enters retirement and is replaced by a far smaller cohort of young people entering the workforce. Therefore, fewer workers must be taxed at a higher rate to cover more retirees or, alternatively, more beneficiaries will be forced to sacrifice more benefits from fewer contributors. In addition, each year that benefits exceed income, as is expected for the first time in 2018, the OASDI reserves shrink, and interest, OASDI’s second-largest revenue source, falls.

Beyond the strain that inaction puts on necessary taxes and benefits, the cost of depletion will be felt immediately and severely. According to a projection from Bipartisan Policy Center’s Commission on Retirement Security and Personal Savings, inaction will cause a 20 percent increase in poverty in 2035 among those aged 62 years and older. Social Security is an essential source of income for retired Americans, and it is no surprise that any reduction in its benefits should have a profound impact.

Solvency Without Breaking the Bank

Beyond cutting benefits and raising tax rates as described above, other means of securing OASDI solvency exist, many of which have backing from both sides of the aisle. The reform most frequently proposed is increasing or eliminating the tax cap. In 2018, the maximum amount of income subject to Social Security taxes is $128,400. Yet, bipartisan research indicates that raising or eliminating the cap could close anywhere from 25 to 90 percent of the solvency gap. Similarly, the Social Security Administration reports that cap expansion or elimination could likely increase the program’s progressivity, or the extent to which benefits increase with an individual’s need, depending on the distribution of newly-available benefits. This option certainly has popular support; 68 percent of Americans favor eliminating the cap completely, the National Institute for Social Insurance found.

Another commonly-proposed reform is to privately invest resources from the OASDI trust fund. Those resources are currently invested in interest-bearing U.S. Treasury debt securities, a low-risk, low-return option. Investing instead in private stocks could prove lucrative, increasing interest revenue and shoring up the trust fund. This idea was unsuccessfully proposed years ago by President Clinton and remains popular today. This solution, however, does not guarantee success: while it could limit how much taxes must be raised or benefits must be cut, it would also introduce risk and possibly interfere with the securities markets.

Similar to the idea of privately investing part of the OASDI trust fund is the establishment of private savings accounts as a substitute for, or complement to, the typical Social Security order. Social Security works under a pay-as-you-go system, meaning today’s worker contributions are today’s retirement and disability benefits, rather than one person’s contributions being saved and accumulating interest until he or she uses them. The disadvantage of this system is that there are no personal accounts, like a personal savings account, to accumulate interest. Converting to personal savings could thus decrease the amount by which taxes must be raised or benefits must be cut in order to preserve solvency without affecting standards of living. Still, personal savings accounts, like privately-invested resources, come with greater risk and move social security away from an insurance plan and toward a savings program alone.

Many other methods exist for protecting the OASDI trust fund. Raising the retirement age, for example, would incentivize work and disincentivize early benefit take-up. Likewise, welcoming immigrant labor by replacing DACA would secure greater tax income for the system. No solution to the Social Security shortfall comes without a cost. But as the looming depletion date approaches and the sacrifices necessary to secure solvency increase, alternatives to raising taxes and cutting benefits become more appealing.

Image Credit: Flickr/401(K) 2012