Earlier this summer, the University of Michigan unveiled the “Go Blue Guarantee,” its new financial aid program. Advocates say it could revolutionize college admissions for low-income students, as the guarantee promises to completely cover up to four years of tuition for undergraduates from Michigan whose families earn less than $65,000 annually. That number, by no coincidence, just exceeds the state’s median family income, $63,893, meaning over half of Michigan families qualify for the program.

While much attention has rightfully been given to this impressive offer, the guarantee extends beyond financial aid. It also introduces a new system of marketing—one that aims to reach talented, low-income students who might otherwise not have seen higher-education as an attainable next step.

Financing the guarantee

Following a 40 percent drop in state funding over the past decade, Michigan now receives just 16 percent of its general fund from the state. This sharply distinguishes Michigan’s financial aid plan from other “tuition-guarantee” programs which rely more on funding from the state than their own internal financing. The state of Michigan gives U of M students who qualify for aid an average of only $715—for comparison, California gives UCLA students an average of more than $10,000. One of the regents of the University of Michigan, Mark Bernstein, stated after voting for the guarantee, “We are doing the job that Lansing and Washington have failed to do.”

The university has also managed to avoid passing on the cost to middle- and upper-class students. This year’s tuition hike of 2.9 percent for most in-state undergrads is less than the 4 percent average tuition growth rate for in-state students over the last decade. Additionally, aid is still abundant for those above the $65,000 threshold required to qualify for the Go Blue Guarantee; 96 percent of in-state students with family incomes between $65,000 and $95,000 receive aid, and none of that aid will be cut to finance the guarantee.

The guarantee doesn’t come without a cost—student aid accounts for about a fifth of the University’s entire endowment. Donations to the non-general endowment also play an enormous part. Of its $4 billion fundraising campaign, Victors for Michigan, about a quarter will go directly to student support.

Still, despite cuts to state funding and the financial aid expansion, a program like the guarantee isn’t affordable only to large universities like Michigan. While the guarantee requires a financial aid endowment large enough to make college affordable to low-income students, the most innovative elements of the program are not matters of finance but matters of marketing.

The role of marketing

With the promise of free tuition, the university focuses on encouraging low-income students to apply. To do this, Michigan presents itself as simply and unambiguously affordable to even the poorest of students. A higher-education is guaranteed, and all anyone has to do is apply.

High-achieving low-income students don’t apply to selective universities as often as their more affluent peers. In part, this is practical, both because lower-income students face greater pressure to earn money and because many universities are simply too expensive. But research shows that these students are often unaware of the affordability of high-quality schools with generous financial aid programs. This discourages them from applying to schools that are, realistically, within their reach. While an unfortunate tendency, this bears a silver lining: expanding information about the affordability of schools with aid could encourage low-income students to apply in much greater numbers.

The university tested this theory through a 2015 pilot study called HAIL, which stands for High Achieving Involved Leaders. HAIL promised low-income, high-achieving students four full years tuition free upon acceptance to Michigan. To test the effectiveness of marketing techniques, experimenters divided eligible students into two groups, a control group and a treatment group. The control group was left to discover financial aid offerings through standard marketing techniques, either by spotting a notice in the university’s standard mailing, by visiting the Michigan website on their own initiative, or through a college counselor, should the counselor be sufficiently informed. The treatment group, however, faced a new marketing strategy which advertised HAIL through simple messages, easy instructions, and direct contact with the applicant. Susan Dynarski, a professor of economics and education at Michigan whose research helped design HAIL and later the Go Blue Guarantee, calls this “tailored outreach.”

Tailored outreach means removing the barriers which often impede low-income students from applying. Michigan did that by, among other things, providing a step-by-step application guide to avoid confusion, distributing vouchers to cut down on the costs of application, and highlighting words like “free” to overcome dubiousness on the part of the applicants. Preliminary results from the pilot study are encouraging: students from the treatment group were around 2.5 times more likely to apply to U of M than those in the control group. These results convinced the university to go a step further with the Go Blue Guarantee.

The “Guarantee”

Michigan’s experimentation with financial aid programs proves a point to other schools: expanding college access to low-income students is more than a battle of dollars and cents. While the guarantee expands financial aid eligibility, it doesn’t do so immensely—Michigan allotted almost as much of its fund to financial aid before the guarantee as it will now. Coupled with the changes in marketing, however, this expansion should be effective. The extra funds allow U of M to make their pitch perfectly clear: earn less than $65,000 and you go tuition free.

HAIL and the Go Blue Guarantee owe much of their marketing design to a 2013 report from economists Caroline Hoxby and Sarah Turner. The report shows how much progress can be achieved through strategic marketing. Several components of HAIL and the Go Blue Guarantee borrow directly from that report, providing evidence of those theories for other schools to consider.

The guarantee, for instance, focuses on advertising what Hoxby and Turner call the college’s “net price,” rather than its listed price. While a Google search of Michigan’s tuition rate might discourage low-income students from seriously considering the university, the guarantee advertises a completely cost-free tuition for qualifying students. This emphasizes the “net price” for tuition—zero—over its listed price of a few thousand dollars. Though many low-income students could have received free tuition under previous aid programs, the guarantee should encourage more students to take advantage of that offer by focusing on clarity. “That was one of the key things,” said Professor Katherine Michelmore, one of HAIL’s primary researchers, in an interview with the HPR. “We want to give them a concrete message about how much they should expect to get.”

Another method suggested by Hoxby and Turner that HAIL tested is to provide application vouchers for low-income students rather than requiring them to apply for fee waivers, which can be a long and confusing process. “We concretely told the treatment group ‘this is what you’re getting’ whereas the control group would have had to go through some more “work” to see if they were eligible,” Michelmore said of the HAIL program. Evidently, being blunt and straightforward made a big difference.

The guarantee also attempts to make it easier for the university to reach geographically-dispersed students. That’s because high-achieving low-income students tend to be much more spread out than their wealthier peers. This makes conventional college recruitment techniques, such as sending a representative of the college to speak directly to high schoolers, ineffective in poorer areas. Hoxby and Turner therefore suggest avoiding this type of recruitment and instead focus on contact with the students or their parents, which Michigan will do by mailing packets advertising the guarantee.

Hoxby and Turner caution against relying on counselors as resources for low-income students with their eyes on selective colleges. Because fewer students from low-income areas attend selective schools, counselors frequently lack experience preparing students for such competitive applications. The guarantee will avoid reliance on counselors by sending mail not only to the schools, but also to the students and their parents directly. “Our strategy was to address any potential pathway that could be a barrier,” Michelmore explains. “We’re hoping a long-term benefit of this is that it will raise awareness to low-income students that they can do this too.”

One piece of advice from Hoxby and Turner was not adopted by U of M because it cannot be adopted by any single university. They suggest that a central organization like the College Board should advertise financial aid opportunities to low-income students in order to lend credibility to the offers. While recognized names like Michigan might not struggle with this issue, smaller and lesser-known schools do. Students know that schools have interest in attracting more applicants, and so they are suspicious of these schools’ financial aid advertisements. An unbiased, central organization can eliminate this problem.

Michigan, however, is showing the impact a single university can have. There is also good reason to believe the guarantee could positively affect more than those who actually attend U of M. “Some of these students, maybe they didn’t know anybody who went to Michigan, maybe they didn’t know anybody who went to college” Michelmore explains. “We’re hoping a long-term benefit of this is that it will raise awareness to low-income students that they can do this too.” There is overwhelming evidence that the proportion of a student’s peers attending college influences that student’s likelihood of doing the same. By expanding college accessibility to areas of the state where higher education is less common, the guarantee could have somewhat of a domino effect, inspiring many more students to gear toward college.

Mark Schlissel, president of the University of Michigan, likes to say “talent is ubiquitous in our society, but opportunity most certainly is not.” The challenge for top-tier schools like Michigan is to match talent with opportunity. That requires more than student aid. Rather than playing a passive role, U of M is actively seeking out talented students who may otherwise never reach their potential. If the results of the guarantee match the results of its pilot program, this program could represent a huge step toward diminishing the income disparity in college attendance.

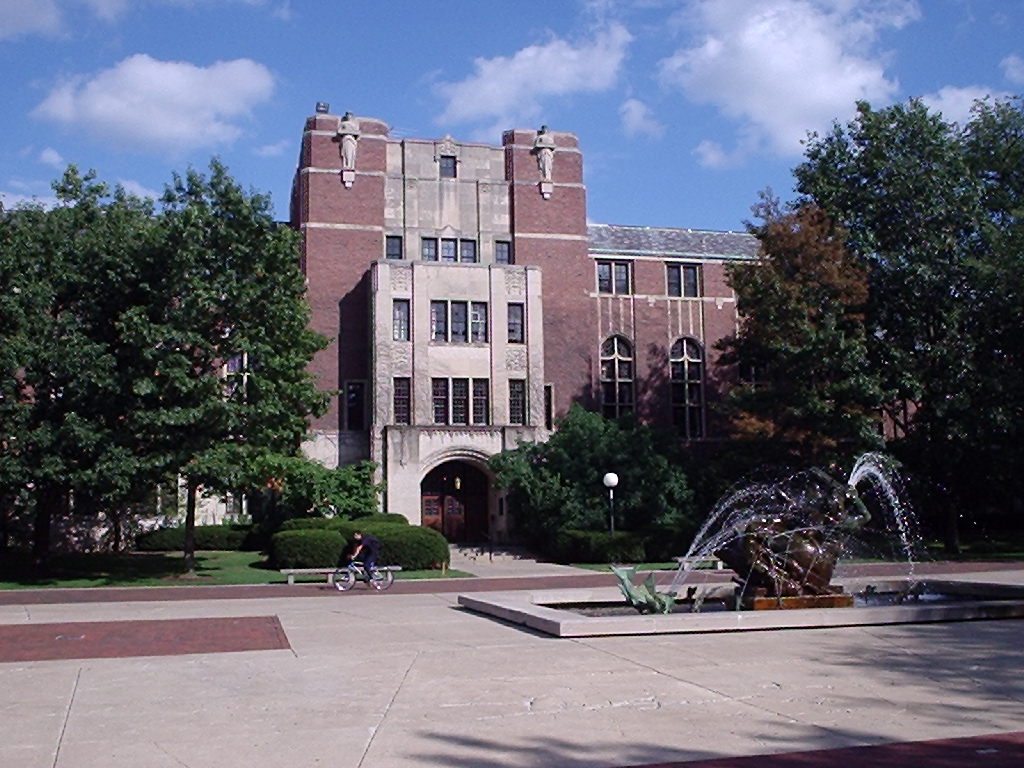

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons