Americans listening to the speeches at the Republican National Convention in July could be excused for thinking the United States was coming apart at the seams. Speakers preaching fear, decay, and lost greatness tugged at the heartstrings of attendees and viewers. Although the speeches were certainly laced with bombast, the core message was not inaccurate.

The summer of 2016 has forced old questions of national life to resurface. Perceived political injustice, racial tension, and economic stagnation will weigh on the minds of voters in November. Although it may feel like the United States is on the brink, the nation has actually been in a similar position before. The turn of the 20th century, notable for the Gilded Age and the eventual launch of the progressive movement, suffered from many of the same issues that dog the nation today and—because of this—might offer solutions. In examining our own situation, we ought to study the plights of a century ago.

Political Decay

Both of the main candidates in the 2016 election have the lowest favorability ratings in modern history. These ratings ride partially on the increasingly polarized American political landscape. Every issue, from climate change, to gun control seems to toe strict political lines. Likewise, according to a Pew Research study, partisan antipathy between the two parties has ballooned; the share of Republicans who have very unfavorable opinions of the Democratic Party has jumped 26 points in the last 20 years, reaching 43 percent. Similarly, the share of Democrats with very negative opinions of the Republican Party also has more-than doubled, from 16 percent to 38 percent.

Americans from all political backgrounds feel increasingly antagonized by their opponents, and they’re looking for someone to blame.

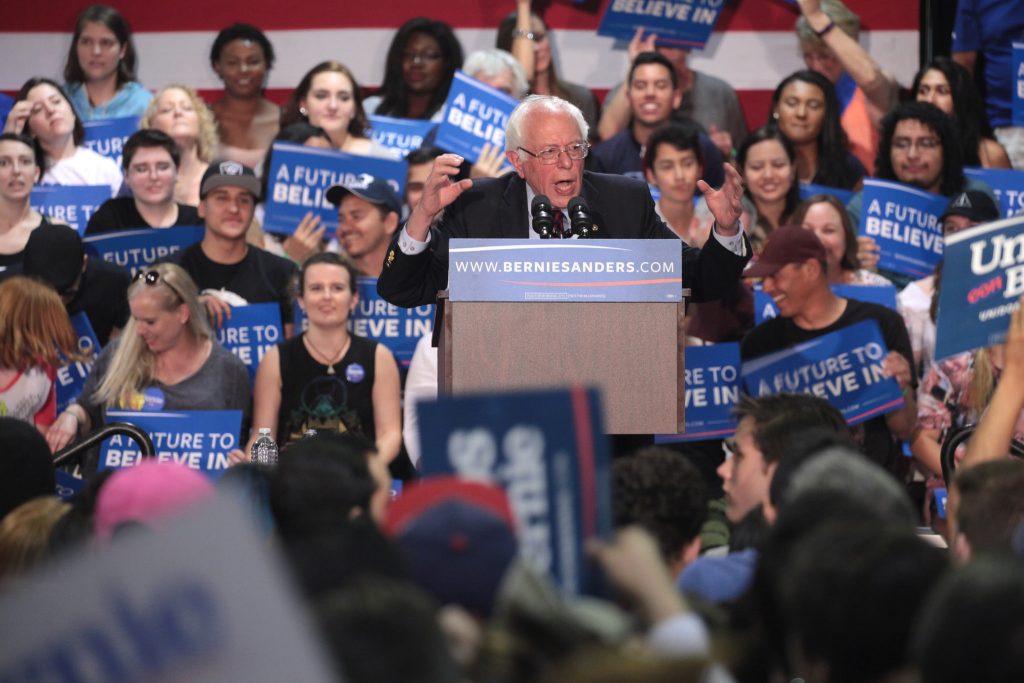

A study by Princeton professor Martin Gilens and Northwestern professor Benjamin I. Page concluded that American democracy was “seriously threatened,” and that “policymaking is dominated by powerful business organizations and a small number of affluent Americans.” It found that policy changes wanted by the majority of the public were only successful about 30 percent of the time, while policy changes wanted by a majority of the wealthy were successful about 60 percent of the time. Moreover, the report concluded that “the preferences of the average American appear to have only a minuscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy.” This knowledge, coupled with unlikable candidates, unfair practices by the DNC and RNC against candidates Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump, and intense animosity toward political foes, has contributed to historically low trust in the government.

Racial Tension

While the week of July 4 got off to a celebratory start, it certainly did not end that way. Two African-American men, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, were shot dead by police, inciting yet another round of racial protest across the nation. Shortly after one peaceful protest in Dallas, five police officers were shot by a lone gunman as retribution. A week later, three more officers were shot in Baton Rouge.

Trends in police use of force seem to debunk the common myth of post-racial America. A poll by PBS and Marist College concluded that over half of Americans believe that race relations are getting worse, with an overwhelming majority of Blacks and nearly half of Whites reporting that African-Americans have a harder time getting a job and achieving equal justice. Statistics show that blacks are 2.5 times more likely to be shot and killed by police and six times more likely to be incarcerated than whites.

Other minorities also feel like they have been treated unfairly. During this election period, nativist sentiments from Donald Trump’s support base have reached the national theater. Apart from expressing support for the birther movement, Trump has taken numerous controversial positions against minorities, from calling for a ban on Muslims and including anti-Semitic symbolism in a campaign post, to advocating the deportation of millions of illegal aliens (we need not revisit his comments on Mexican “rapists” and “murderers”).

Changing Economy

As the world becomes increasingly globalized, the role of the United States in the international economy is changing noticeably. The once large manufacturing sector has given way to a dominant service economy, requiring more highly-educated and highly-skilled workers. Although the new economy has ushered in higher wages for some, many low-skilled workers, whose jobs have been shipped abroad, feel disaffected.

But even service laborers who have worked their way up to the middle class have been feeling economic pressure. According to a Pew Research study, real wages—that is, wages adjusted for inflation—have not increased for decades, even though worker productivity over that same time period has increased by about 80 percent. As Chris Matthews from Fortune Magazine put it, individuals who “had been taught to expect their material wealth to grow through their lifetimes and across generations, [have] learned that this promise was a lie,” paving way for “radical politics and specious solutions to their economic problems.”

In order to find where all the new wealth has gone, you must look up. While wages across the board have idled, the fortunes of the wealthiest Americans have buoyed. According to findings from professors Peter Lindert and Jeffrey Williamson in their book, Unequal Gains, income inequality today may be the highest in history. Yes, even higher now than it was during the famous Gilded Age from the late 1800s into the 1900s— the age of famous multimillionaire and billionaire Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller.

Progress Means Looking Backward

The turn of the 20th century may have more to offer than the philanthropic remains of past millionaires, and the extravagant mansions dotting the Rhode Island coast. The Gilded Age—a phrase coined by Mark Twain in reference to the thin façade of wealth that masked the true condition of American life—was also known for its crooked politics, racism, and concerns about a rigged economy.

Political life was synonymous with corruption during the Gilded Age. Due to a lack of welfare and social services from the government, organizations sprang up to meet the needs of the urban poor. Some of these organizations, like the infamous Tammany Hall run by William M. Tweed, were tied to the Democratic and Republican parties. “Boss Tweed” worked his way up the political ranks to obtain powerful positions within the Democratic Party of New York. From there, he used his office to have his candidates elected to high positions, establishing the “Tweed Ring,” and he proceeded to amass a fortune with his partners. By granting favors and political positions in exchange for support, organizations such as Tammany Hall were able to hijack municipal governments with corrupt machine politics and strongly favor business interests, accepting bribes and kickbacks in return.

Sentiments towards immigrants and blacks were no less problematic. The U.S. was experiencing record high immigration, with many newcomers from Eastern and Southern Europe as well as China. Americans with origins from Western Europe, and mainly white, Protestant males, saw these immigrants seen as a threat to the traditional American way of life, and to their jobs and incomes too. Nativists pushed for restrictions on immigration, ushering in laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act, and magazines regularly published racist propaganda. Populations within the United States also found themselves in transit—the Great Migration brought many African Americans out of the South, to industrial cities in the Northeast and Midwest. Race riots and mass attacks on black citizens broke out in major cities, and police forces were either directly involved or else had turned a blind eye.

Industry, meanwhile, posed a problem for American workers. Monopolies dominated labor and infiltrated governmental affairs to ensure their success by circumventing regulation and price gouging essential goods and services. When workers tried to strike or organize, businesses often went to court to stop them. Fearing for their jobs, workers had no choice but to toil long days— at least 60 hours a week with no benefits. While the wealthy were able to amass huge fortunes, the average worker lived in crowded, unsanitary slums.

Progressive Precedent

Out of the troubles of the Gilded Age, the American Progressive movement was born. Progressives, as they came to be known, dedicated themselves to bringing about reform and regulation. Their goals were to improve the quality of life for the poor, police big business by standing up for workers’ rights, end government corruption, and help integrate immigrant communities. The tactics that the Progressives employed might provide answers for contemporary reformers looking to remedy similar problems in modern America.

Though many are unaware of its agrarian origins, the reformist movement began with angry farmers in the late 1800s. Trying to profit from their crops, these farmers sought to purchase machinery and land from big businesses. However, due to high mechanization and transport costs, the farmers fell into tough financial times. They organized into what became known as the Populist Party. Much like the Bernie Sanders camp, supporters demanded regulation of business, increased public service for the poor working class, increased welfare, and thorough political reform for a system that they saw as corrupted.

While the Populist Party’s candidate, William Jennings Bryan, lost the election in 1896, the progressive movement had only just hatched. In the years to come, the bulk of progressive publicity came from “muckrakers,” or reporters and journalists who exposed social ills in their writing. Authors like Upton Sinclair, Ida Tarbell, and S.S. McClure unearthed deplorable working conditions in American factories (famously in meat packing plants), criticized the Standard Oil monopoly, and exposed the harsh conditions in the slums.

Many readers, inspired by the muckrakers, rallied to the progressive cause. Progressive reformers came from every occupation–politicians, teachers, clergymen. These progressives passed laws to curtail the spoils system by requiring that those appointed to government jobs pass an examination, and by inducting the Australian ballot which required that voting be conducted in private in order to eliminate voter intimidation.

With a faithful activist base, progressives began to run for local public office and spark change from the inside, an initiative met with great success. Americans approved of the work of the Progressive politicians at the local level so much that they continued to vote for them in increasingly more powerful positions at the state and national levels. From governors like Robert La Follette, to the “trust-buster” Theodore Roosevelt, progressive public officials succeeded in passing laws that reshaped the country.

All the while, progressives had also worked to address the problems of African Americans and immigrants. African American progressives picked up the fight to end segregation and Jim Crow laws by forming the NAACP. Black journalists like Ida Wells challenged discriminatory policies and protested the lynching of black men. Other black progressives like Booker T. Washington advocated for greater education and self-improvement to advance the standing of black people; while W.E.B. Du Bois demanded and created plans for complete and instant equality, as he believed that self-improvement would only occur if blacks were politically and socially accepted and equal under the law.

On the immigrant question, progressives believed that newcomers would not be able to successfully participate in civic life unless they felt American. Progressives embraced efforts to teach English and American civics and to provide professional training and health services. Compulsory public education (which now included kindergarten) were tasked with teaching these courses.

Patriotic expressions, such as a daily flag-salute at public schools, aimed to promote loyalty to a unified nation. Flag day was started to honor the birth of the American flag, and President Theodore Roosevelt advanced martial patriotism alongside civic patriotism to inspire awe for American soldiers. Christian socialist minister Francis Bellamy joined this patriotic movement. He sought a new America, free from the unrestrained greed that he thought gripped the nation, and wrote the Pledge of Allegiance hoping that it would unite Americans under a common moral goal to work for a more equal and fair life for all citizens.

Progressives politicians spurred a laundry list of business reforms, from curtailing child labor to drafting the 16th Amendment allowing Congress to levy an income tax and passing food inspection laws. While President Wilson worked to protect the consumer by regulating railroad, gas, electric, and telephone utility rates, President Roosevelt broke up big business monopolies and trusts to spark capitalistic competition as part of his drive for a “square deal.” Other Progressives chose to work directly with the urban poor, like Jane Addams who founded Hull House, a settlement house where the poor could go for social and educational assistance.

Now, It’s Our Turn

We can learn something from the progressives of the 20th century.

The political, racial, and economic climate of modern day America is very similar to that of the Gilded Age. Black men and women still confront a skewed criminal justice system. Major national politicians continue to blame immigrants for many of the nation’s problems. Democratic and Republican politicians still seem beholden to the interests of corporations in the aftermath of Citizens United. Workers may not be forced to toil inhumane hours, but poverty and income inequality has risen to the highest level in 40 years.

Populism and progressivism, which cater to the needs of the worker, the immigrant, and the average American, might offer the fix to many of these problems plaguing America today. As seen with the populist movements in this 2016 presidential election, a spirit of reform—one that works to build a more unified nation, and one that works to bring people from all ethnicities and political backgrounds under one banner—might once again be underway. In the coming years, it will be up to progressives to continue the work that the Bernie Sanders campaign started in order to pave the way for the next Progressive Era.

Image Credit: Gage Skidmore/Flickr