This article was co-written by Chloe E.W. Levine and Oliver York.

Espousing — no, exuding — patriotism has been a tacit requirement for U.S. presidential campaigns since the dawn of the nation, even as debates about the true meaning of patriotism have embroiled candidates. Who could forget the 2008 scandal in which then-Sen. Barack Obama, D-Ill., decided to forgo a flag pin and sparked a national battle over the very definition of patriotism? Unlike in 2008, however, in 2020, winning the right to call oneself a patriot may not mean winning the election.

In fine-tuning their formulas for success, candidates that hope to win the youth vote must tread cautiously around the topic of patriotism. Amidst plummeting levels of national pride, invoking patriotism may still prove viable, but only if handled with care. Young Americans’ responses to questions about their patriotism vary based on the specific words used to ask them. Understanding these discrepancies could provide valuable insight into the dimensions of young voters’ love for their country, helping campaigns calculate how best to harness that love in the name of victory.

Words Matter

For many young people, patriotism holds some appeal, but self-identification as a patriot would be a bridge too far. A recent poll of 18- through 29-year-old Americans by the Harvard Public Opinion Project finds that they have drastically different reactions to the words “patriot,” “patriotic,” and “patriotism.” When asked which from a list of ideological monikers (patriot, socialist, capitalist, democratic socialist) they identified as, if any, 33% of the HPOP poll’s respondents claimed the label of “patriot.” Respondents were much more likely to consider themselves “patriotic,” with a total of 62% describing themselves “very” or “somewhat” so. The popularity of patriotism as a concept falls between those two rates: Presented with the same list in noun form and asked which schools of thought, if any, they supported, 52% of respondents expressed support for patriotism. Significant contingents of young people polled, then, would call themselves patriotic despite a lack of support for patriotism or a refusal to self-identify as a patriot, revealing prevalent ambivalence about these words and the ideologies for which they stand.

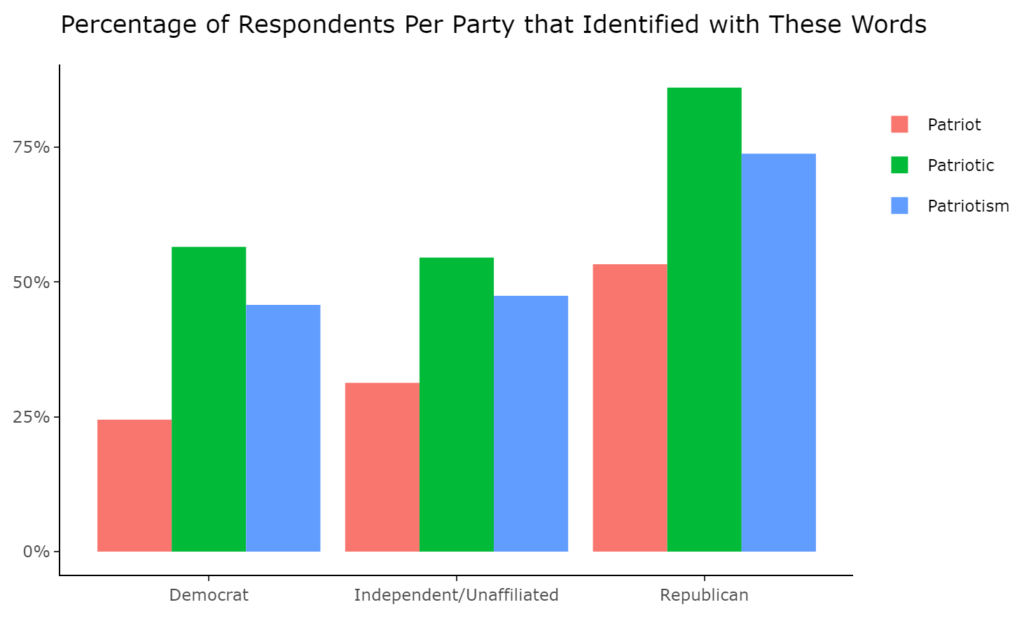

These trends in respondents’ relative reactions to different word forms characterize the HPOP data across party lines. Political parties undoubtedly grapple with patriotism in different ways: Republicans are, on balance, more enthusiastic about their national pride, while Democrats emphasize constructively criticizing the nation in order to improve it. Nevertheless, members of both parties seem to associate their preferred politicians with the term “patriotic,” implying that they view the adjective positively. For example, 35% of Democrats said Republican President Donald Trump was patriotic, compared to 87% of Republicans, and 39% of Republicans said former Vice President and current Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden was patriotic, compared to 69% of Democrats. Indeed, for both Democrats and Republicans, respondents were most likely to identify as patriotic and least likely to identify as a patriot, with 33 percentage points separating the two figures. A parallel trend held for respondents not affiliated with either major party. These findings suggest that candidates of all party affiliations should pay attention to the nuances inherent to potential voters’ understanding of patriotism.

Nationalism and Patriotism

The connotations of right-wing nationalism carried by some iterations of patriotic language today help to elucidate the HPOP results. President Trump frames his political movement as a defense of American pride, expressing affection toward patriotic symbols and using the slogan “Make America Great Again” to encourage nostalgia for American history — although that history is inextricably linked to oppression. He unabashedly ties his version of patriotism to a controversial brand of nationalism which puts “America First” in a militaristic foreign policy agenda and often rejects the value of international cooperation. In just one example, the disastrous outcome of the Trump administration’s individualistic response to the coronavirus has demonstrated that “America First” is a clearly fallible strategy for ensuring the wellbeing of Americans. Still, by his definition, globalists and patriots are opposites. Due to this widespread conflation of patriotism and nationalism, even academics struggle to articulate the contemporary difference between the two in the United States. Consequently, many Americans perceive a connection between the application of patriotic ideology and violence, discrimination, and division.

Labeling oneself as a patriot is therefore ambiguous: Do self-identified patriots view themselves as Trump-era nationalists or idealistic critics? Is their love of country unqualified or aspirational? Adopting such a label without an explanation may feel risky, since psychological studies have found that labeling a person unleashes an arsenal of associated assumptions upon them. Coupled with the diminishing importance of patriotism in the daily lives of young Americans, professing personal patriotism distinct from nationalism may not seem worth the potential misunderstanding. This effect could explain respondents’ reluctance to call themselves patriots in spite of their support for depersonalized patriotism and claim of the adjective “patriotic,” which from a linguistic perspective partially modifies their identity rather than definitively characterizing it.

The Need for Nuance

Attesting to a belief in patriotism is made more difficult by the ideology’s wide-ranging definitions, imprecision which could make even Trump voters feel uneasy about an admission of support. The McCourtney Institute for Democracy’s June 2019 Mood of the Nation Poll reveals significant variance among respondents about patriotism’s defining characteristics. The component most commonly agreed upon was “showing respect, loyalty and love for one’s country,” but there are multitudinous possibilities for the real-life manifestations of that quality. An almost contemporaneous Economist-YouGov poll found similar disagreement. In one particularly stark difference, Democrats were 37 percentage points more likely than Republicans to allow that an American could be patriotic despite “refusing to serve in a war that they oppose.” Democrats were also more likely to accept a similar allowance for Americans who “disobey a law they think is immoral,” though with 56% of them in support as compared to 41% of Republicans, both groups were divided. The relationship between patriotism and morality is thus unclear; some see the two as inextricable, while others believe patriotism can require immorality. All these discrepancies suggest HPOP respondents unwilling to brand themselves as patriots/patriotic or support patriotism might have been deterred by uncertainty about the literal terms of the question.

It follows that when given the option to place themselves along a spectrum of patriotism, respondents were more willing to identify as at least somewhat patriotic than they were when given a binary choice between support and disavowal of the ideology. According to the HPOP data, the highest rates of patriotism were derived from the net affirmative responses to a question which asked young Americans how patriotic they considered themselves to be (very, somewhat, not very, or not at all). Respondents nervous about the implications of an unconditional affirmative answer could, in the adjectival form of the question, answer with reservation. This result indicates that politicians would be electorally ill served by presenting a monolithic, all-or-nothing patriotic vision.

For 2020 candidates, then, the solution to this ostensibly conflicting data could be simply broadening campaigns’ definitions of patriotism. Young Americans disagree about the parameters of patriotism, and their responses suggest apprehension about the ideology’s associations, but a clear majority express some measure of interest in patriotic thought. Appealing to that interest thematically — without getting bogged down in the hackneyed language and cliched iconography with which discordant ideas about patriotism are so often wrapped up — might just earn candidates the votes they need.

Image source: Flickr/WEBN-TV