While most outside reporting on Mexico is currently focused on its upcoming presidential election, the country is currently undergoing a major economic transition. Namely, major supply chain issues are barring the country’s approximately one million micro-businesses, or tienditas, from reaching profitability and sustainability in their efforts to service the over-100 million citizens that rely on them. Unlike in the United States, most areas of Mexico have historically had few major wholesale conglomerates; thus, over a million of these tienditas have opened shop throughout the country.

Now, as they begin to face new competition from growing conglomerates like Oxxo, 7-Eleven, and Walmart, these tienditas struggle to gain collective bargaining power over such major wholesale providers, and they also suffer from the endemic challenges of an extremely inefficient and expensive supply chain. Approximately eight Oxxo stores open every hour in Mexico, causing about five small businesses to terminate operations. This, coupled with significant productivity declines in the traditional sector, has wreaked havoc on the hopes of many retail-oriented entrepreneurs.

Ultimately, supply chain inefficiencies have created an unfavorable environment for small businesses in Mexico. As large conglomerates begin to compete with these tienditas, the health of the small business economy throughout Mexico is at grave risk, which puts the nation’s overall growth and prosperity in jeopardy. Small business support from the government and private sector could alleviate this issue, but an ultimate fix might lie in the improvement of the Mexican supply chain at large — the introduction of more “middle men” to facilitate more efficient connections between tienditas and major goods providers.

Fighting for the Small Guy

It is no secret that there is a plethora of small stores throughout Mexico, particularly in Mexico City. In an interview with the HPR, Rodrigo Sanchez Gavito, co-founder of Tenoli, stated that there are almost 100,000 of them in Mexico City alone. Tenoli is a new and growing social enterprise that works to support tienditas through network-building, distributional services, and growth-centric consulting.

While the stores in the City have few issues with foot traffic and customer acquisition, both urban and rural stores confront major challenges with efficiency and profitability. In essence, the logistical aspects of storing inventory and transporting it to these tienditas are impeded by a lackluster capacity for supply chain management. According to Sanchez, these stores lack proper shipping capacity, accurate product demand forecasting technology, and warehouse management.

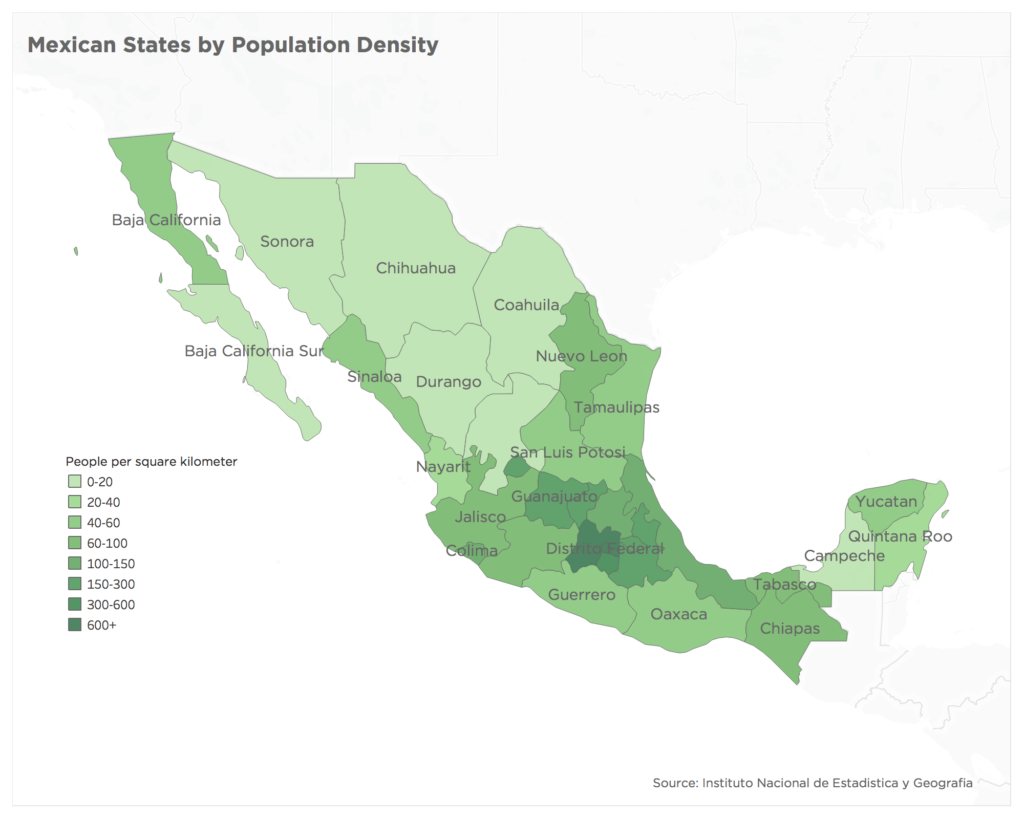

Moreover, rural areas face the particular issue of massive population dispersion, greatly exponentiating their supply chain inefficiencies. As the map below shows, the majority of the Mexican population is concentrated around a few urban population centers; however, most of the country’s northern states have populations scattered across large areas. For the thousands of tienditas in the north, supply chain issues are exacerbated by the distance that goods need to travel to reach them.

Beyond the supply chain, Mexican tienditas lack the ability to collectively bargain for favorable prices from producers. According to Sanchez, “a major challenge for the tienditas is to compete as a network with the modern sector.” These dispersed and separate entities struggle to foster profitable conditions for business because they negotiate individually with large-scale producers.

Attempts at Modernization

All of these factors have greatly increased costs for Mexican small businesses both inside and outside of Mexico City. This puts them at a great disadvantage as Oxxo, Walmart, and 7-Eleven locations open in every corner of the country. As Sanchez says, “none of these microbusinesses have the resources to compete against these modern conglomerates”; they need a fundamental transformation in the way they operate.

Such a modernization will not be easy. It represents a huge transition in the way Mexican businesses operate. Organizations like Tenoli, run by Sanchez, have begun to support tienditas by increasing their bargaining power over large, corporate providers, like Procter & Gamble, and by creating more efficient supply chains through collaboration and the roll-out of electronic transaction technology. Nevertheless, even smaller chain stores, like Scorpion, are still being stifled by the introduction of these large, multinational corporations.

According to Sanchez, one reason for this is that “many Mexican citizens simply prefer shopping in the modern sector over the more traditional sector” — an issue common in America as well. Furthermore, a gap in productivity growth between these two sectors has deterred investment in traditional tienditas as well. According to a report by McKinsey & Company, while Mexico’s modern businesses have seen annual productivity growth of 5.8 percent in the last few years, among traditional firms it has fallen by around 6.5 percent annually.

Ultimately, the large performance gap between the Walmarts and the Scorpions of Mexico has combined with huge divides in terms of profitability and supply chain management to stifle any hope of survival for many small companies.

Natural Death or an Economic Catastrophe?

To Harvey Powell, a former business executive and resident of Mexico, this is part of a natural evolution, a “creative destruction” working to modernize the Mexican business environment. “What you’re seeing here is not a new phenomenon. This is a trend that started decades ago in America and has been seen all around the globe.”

However, many scholars studying this issue point to factors that make the Mexican situation unique. In an interview with HPR, Ximena Castañon, a Masters candidate at the MIT Supply Chain Management Program, stressed that “throughout Latin America, there is a huge entrepreneurial culture out of necessity.” Unlike in the United States, many Mexican entrepreneurs are motivated by financial need — not a risk-taking, innovative impulse.

As Castañon’s colleague, Rafaela Nunes, put it in an interview with the HPR: “In America, entrepreneurs are mainly post-MBA grads who saw opportunity. In Latin America, entrepreneurs are predominantly the people who lost their jobs and don’t know what to do and start a business.” Therefore, the destruction of these businesses could be catastrophic for certain lower-income portions of the population.

To clarify, Mexico is by no means failing economically; it is one of the fastest growing emerging markets in the world. Bloomberg News ranked it as the 16th top emerging market in 2013, and it has seen GDP growth rates on par with those of the United States since then.

However, macroeconomic factors are not always proper indicators of the overall picture of a country. While modernizing, export-oriented industries have brought investor attention to the Mexican marketplace, the country’s standard of living still greatly lags behind that of other nations. According to the Better Life Index, an international comparative analysis done by the OECD, while “Mexico ranks above average in civic engagement and subjective well-being,” it lies “below average in the dimensions of jobs and earnings, health status, environmental quality, housing, income and wealth, social connections, work-life balance, personal security, and education and skills.”

For store owners, this is a brutal reality. According to this same report, “the average household net-adjusted disposable income per capita is USD 13,891 a year, considerably lower than the OECD average of USD 30,563 a year.” There is also immense economic inequality: “The top 20 percent of the population make nearly 14 times as much as the bottom 20 percent.” In terms of employment, only about 61 percent of people aged 15 to 64 in Mexico have a paid job.

Overall, this economic picture might not be a recession or stagnation on the large scale, but for small-business owners in the traditional sector, rapturous reports of national economic progress ring hollow.

A Path Forward?

As the Mexican presidential election scheduled for July approaches, the front-runner, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, has vowed to enact comprehensive welfare reforms that will support the greatly disadvantaged lowest quartile of Mexican wage-earners. However, not much has been said by any of the candidates on how to fundamentally reform Mexican institutions to prevent this poverty and unemployment in the first place.

The enumerated causes of tiendita stagnation above suggest that only large institutional reforms can save the crumbling traditional sector in Mexico, which will enable these small businesses to actively compete and survive despite the expansion of Walmart, Oxxo, and 7-Eleven.

For many, financial and microlending reforms could be a start. Only 39 percent of the Mexican population has access to a bank account, and 75 million people still have no access to the kind of financial services and lending support they would need to start micro- and small- businesses. Moreover, according to Sanchez, many tienditas lack any sort of electronic financial transaction technology that would help them reverse trends in their productivity growth.

For Powell, however, reform should be focused on retraining education efforts instead of actions to bolster preexisting mom-and-pop stores across the country: “You can’t prohibit a more efficient operation, so there is room for the government to come in and help the displaced micro-business owners. There’s no pipeline to the trades, so the government needs to build this up.”

Ultimately, the solution might lie in coupling the modernization of the traditional retail sector with support and retraining efforts for those who are displaced from the shrinking sector. While Walmart, Oxxo, and 7-Eleven offer the instant gratification of modern commerce, fundamental reform to help hundreds of thousands of Mexican small businesses modernize could alleviate some of the most pervasive inequalities in the country.

Image Credit: Flickr/Eddy Milfort